Not along after Endre Friedmann and Gerda Taro invented “Robert Capa” they established the Atelier Robert Capa on the second floor of this building at 37 rue Froidevaux, (François-Xavier-Eugène 1827-1882, a commander in the Sapeurs-Pompiers, the fire and rescue brigade of Paris), in the 14th arrondisement. It was the closest they ever came to having a home and turns up repeatedly as a touchstone in the invented life of Capa. Most interesting is its appearance in Patrick Modiano’s novella, Suspended Sentences, as the setting for a story about creativity and loss.

I don’t know what was on street level in 1936, now we find a florist and funeral service business because across the street is the cemetery of Montparnasse. That’s where I am, standing on the corner of the rue Émile Richard (1843-1890, a President of the municipal council of Paris), which bisects the cemetery and is now the site of a small tent encampment of the homeless. Several campsites along the street are furnished with modern red office chairs in such good condition they appear to have been recently delivered.

Walk through the cemetery and you come to the Boulevard Raspail, (François-Vincent, 1794–1878, French chemist, physician, and politician), one of the main thoroughfares of Montparnasse.

Turn left on the boulevard and you’ll pass several hotels, a school, and a student residence. Paris is a national education center and the presence of students and scholarship animates and rejuvenates this historical city of imposing architectural monuments. Just a few blocks down is the corner of Boulevard Montparnasse, the site of Le Dôme.

In the thirties this café was the gathering place for the growing coterie of photojournalists who were drawn to the city. Some, like Capa and Taro, were Jews who had fled the growing threat of National Socialism in Eastern Europe; some, like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Willy Ronis, were French who came here to meet with their peers. They were joined by André Kertész, Giselle Freund, David Szymin (Chim), and others in what must have been the greatest gathering of photographic talent ever to grace a coffee shop. Photographers aren’t always verbally gifted but I’d guess the competitive banter of this group was lively and amusing. This was their living room, clubhouse, and office where they met to compare notes on editors and assignments and plan coverage of the great stories of the time.

Cafes had personalities then, created by the crowds they attracted, so while you might find Hemingway and Picasso in a raucous scene at Le Select, Sartre and de Beauvoir would be presiding over a quieter discussion at Café de Flore.

Le Dôme was the home for photographers and, of course, it was a very different place then. Now the interior is an upscale seafood restaurant that smells only of cashmere and money. The terrace is more casual, and more democratic. I’m seated next to a well-dressed man in his sixties (I need to upgrade my wardrobe), reading Racine and taking notes: a professor, I’d guess. Next to him is a younger man intensely focused on his MacBook, and obsessively checking his phone. I’d like to think he’s a lovelorn novelist. Why not, it’s Paris? There are several women of different ages, some alone, some in pairs, all having lunch. A middle-aged couple orders the skate wing lunch special and the novelist another coffee. A young woman with a suitcase orders a café crème, tends to her text messages, and leaves a few extra coins for the waiter. The professor finishes preparing his lecture and relaxes with a glass of white wine.

I order a beer, which comes with a small bowl of olives, then get a little hungry, so I order a sandwich mixte au pain Poilane, without butter (I love this city but don’t want to die here, at least not yet). I ask for a little mustard. It’s a good thing I’m not very hungry. I make a few pictures and a few notes for this essay and order a coffee. I leave an extra tip for the waiter because I think it’s what Capa would have done, even if he had to borrow the money from Cartier-Bresson.

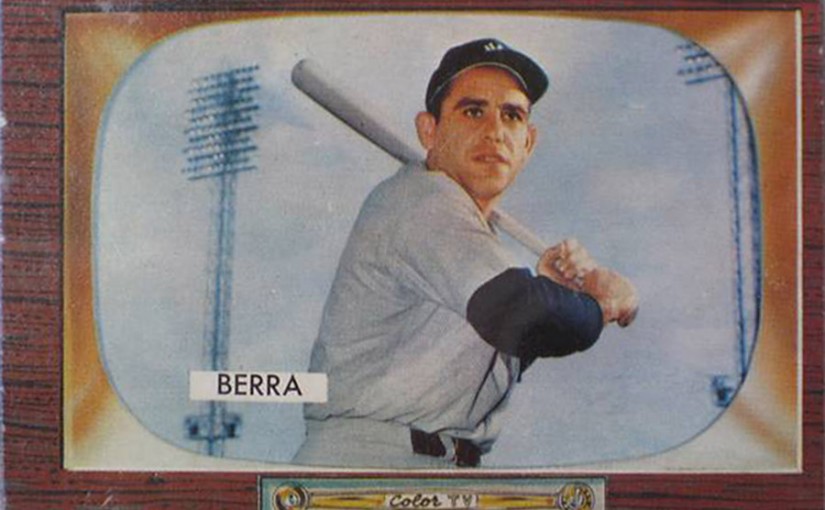

Capa and Taro have gone off to war in Spain. They are photojournalism novices and their quest is not to document facts, but to witness and support Republican victories. Only Capa will return.

I decide to go to Père Lachaise and find Taro’s grave. I ask for directions in the cemetery office but the computer cannot find Taro, then I remember her birth name, Pohorylle, and we get a hit. I’m following my map down a path covered with autumn leaves when I pass an attendant who shouts and points: “Jim Morrison, that way.” I shake my head and walk on.

Taro is buried in a small Jewish section near the Mur des Fédérés, the group monuments to those unidentified souls who died in wars and Nazi extermination camps.

Her tomb is small, much smaller than her neighbors, and plain, adorned only with a simple block with her name and dates, and the Giacometti falcon that was commissioned by the Communist Party hoping to profit from her death, although she was never a party member. Visitors have left a few stones, several painted with the colors of the German flag, although she was not German, and a print of a Capa photo of Taro resting by the side of a Spanish road. Some flowers are long gone, but their plastic wrappers remain.

She’s mostly forgotten now. After she died in Spain, Capa tried to save her work and he probably did, but credits were haphazard. Many old prints bear stamps that say both “Photo Capa” and “Photo Taro,” and many negatives carry no attribution at all. It’s often impossible to know for sure who made the photos, so the credit usually goes to the famous Capa, who might never have achieved that fame if he hadn’t met and fallen in love with Gerda Taro. It’s a subject that is explored in greater depth in Rivesaltes, a novel in progress.

©2015 Ron Scherl

The museum building itself is built into the ground and from above resembles a soaring monument at rest, surrounded by the crumbling barracks and latrines of the detention camp on their way to returning to the earth. There is a path circling the building and, on an overcast day with the wind blowing, you can almost feel what it must have been like to be imprisoned here.

The museum building itself is built into the ground and from above resembles a soaring monument at rest, surrounded by the crumbling barracks and latrines of the detention camp on their way to returning to the earth. There is a path circling the building and, on an overcast day with the wind blowing, you can almost feel what it must have been like to be imprisoned here. The entrance is a long descending ramp that appears to lead nowhere, but turns to the right to reveal a door.

The entrance is a long descending ramp that appears to lead nowhere, but turns to the right to reveal a door.

The main room is divided into sections that tell the story of each of the populations with historical footage projected on the rough cement walls, oral testimonials accessible through tablets, and informational films on video monitors. And there is also a look forward, a consideration of how we will deal with the same issues in the 21st century. The overlapping sounds and the design of the structure itself simulate the lack of privacy in barracks life.

The main room is divided into sections that tell the story of each of the populations with historical footage projected on the rough cement walls, oral testimonials accessible through tablets, and informational films on video monitors. And there is also a look forward, a consideration of how we will deal with the same issues in the 21st century. The overlapping sounds and the design of the structure itself simulate the lack of privacy in barracks life.