It began about five years ago in Maury with a chance remark followed by a visit to an abandoned concentration camp. I stepped past the barbed wire, walked through and around crumbling buildings, made photographs. Then I began to write.

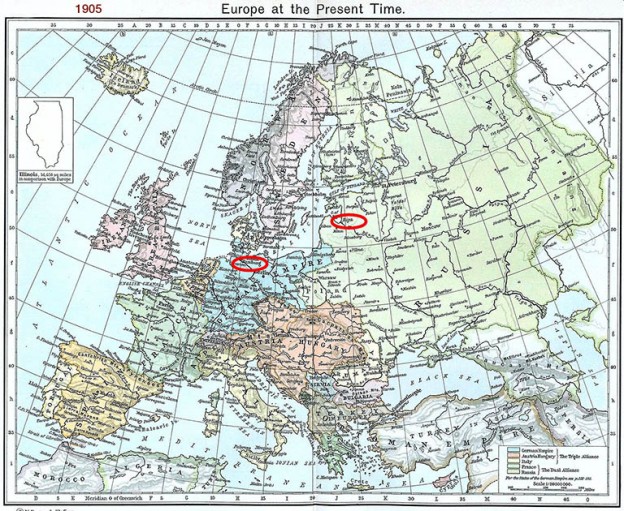

Rivesaltes begins with two historical figures, the photojournalists Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, and continues with fictional characters in stories of three wars that intersect at the Rivesaltes camp and together comprise a fictional history of twentieth century Europe. It is a historical novel, but the stories of refugees created by war have an immediate and emotional connection to the present day.

The novel’s cinematic quality is derived from the pictures of Capa, Taro, and other great photographers of the period. A significant amount of research time was spent examining their images. That was the fun part. And it was a pleasure to work in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, a place that confers serious intent with registration as an authorized researcher. A bargain at eight Euros. The microfiche archives of the Conseil Générale in Perpignan were not quite so enjoyable.

Five years of research, writing, and revising. The first draft came out in a rush. The characters drove the story to places I’d never envisioned, new characters appeared when needed and they took the story in different directions. I was just the guy with his fingers on the keyboard. The story raced to its conclusion and then the hard work began.

Photography is instantaneous. An image may be informed by years of experience but it is created in a fraction of a second that captures a facial expression, the peak moment of action, or the perfect light.

Writing is interminable. Revision on revision, finding the right word, crafting the perfect sentence, molding and shaping until you just can’t do it anymore, and decide to call it complete.

Finished? Only until an editor gets her hands on it. But it’s time to find out if anyone wants to publish it so queries will go out to agents who will say yes, no, or nothing at all. First up is an agent who was considerate and respectful of my first book, although she ultimately decided it wasn’t for her. I came to agree with her judgment and stopped submitting it, but I think there’s some value there and I may yet find the way to make it work. Rejection sucks but it’s part of the deal, much more often than not. The odds are long. Capa rarely had a winner at the racetrack; let’s hope we have better luck in the literary lottery.