Thursday marks one year to the day since I arrived in Maury, a chance to indulge in a bit of reflection. I came here because I had to change and because I thought I could make a book here. The book was to be the story of what happens to a traditional rural village when new money comes in to build wineries and make new “International” wines from the old vines that for centuries have been farmed by local families and delivered to the coop to make strong, if mostly undistinguished table wines and a well known fortified sweet wine that is drunk as an aperitif. I was interested in exploring the downside of globalization by drawing a portrait of a village undergoing radical change from rural and isolated to a “wine experience” where tourists flock to bask in the glory of the latest cult wines. I expected to find that locals were being driven off their land and out of their homes by rising prices. I thought the younger generation would be abandoning the village for the city because they could no longer envision succeeding their parents in the family vineyards. I expected corporate hotels and cute B&B’s to be on the drawing board. So what has happened here? Not much.

Change happens but here, everything happens very slowly. Certainly there is new money being invested in the region and that will have some effect in the years to come, but for now the effect is benign. Dave Phinney, (aka: the guy from Napa) has bought 100 hectares of vineyards that were scheduled to be torn out either because they were not productive enough, or because the family had no one left to farm them. That’s about one million euros into a local economy that sorely needs it. Yes, he’s built a winery that seems designed to keep people away and yes, he makes blockbuster, high alcohol, wines for the U.S. market and he will sell them because Phinney is a master marketer. But who is this hurting? Do other winemakers feel they have to keep upping the ante by making bigger wines to match? I don’t see it. The French don’t feel as if they’re being exploited, on the contrary, they argue that all publicity is good and all Maury winemakers stand to profit if the town becomes better known in the wine world.

This is arguable of course, but the mayor, an incurable optimist, believes that change can be managed. He foresees a time when as much as 50% of the vineyards might be owned by outsiders and a free interchange of skills and ideas benefits everyone. That’s a tall order but Charley has the combination of warmth and charisma that makes you want to believe. We’ll see.

There are others here now and they all add something a little different: Marcel Buhler has gone from being a Swiss banker to an organic wine grower. Katie Jones is getting good press for her wines. Eugenia Keegan just bought some vineyards. There’s a group of Mexican vintners just over the hill and Chapoutier from the Rhone just released his first Roussillon wine in the US.

All of this activity has taken place in the last ten years but there aren’t many obvious signs of change in the village. There are about thirty independent wineries in town and more often than not you’ll find multiple generations working together. The coop membership has stabilized with about 130 growers and a goal of making equal amounts of sweet and dry wines. I’ve recently been working with a marketing committee there composed of three men and two women all in their 20’s.

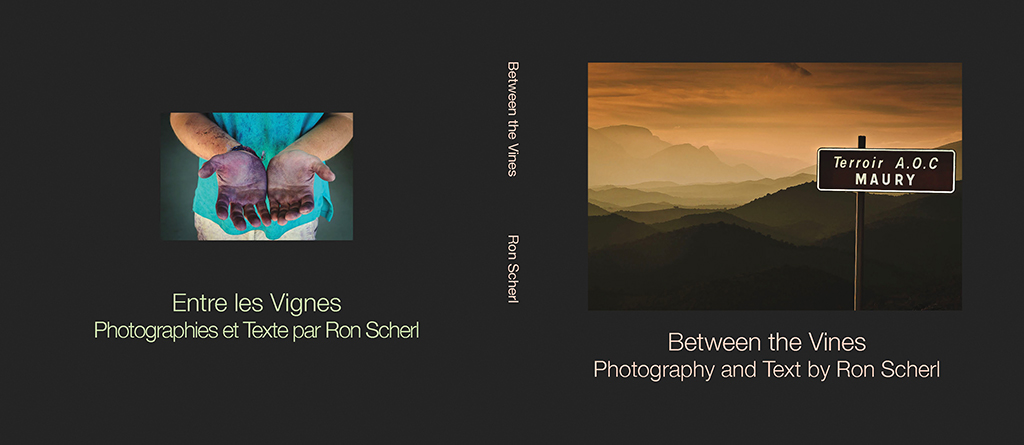

So change is slow and the book I envisioned is not going to happen, well it might be done some day but not by me. I think the impact on the village of the new wineries of today is twenty years away from being evident. I don’t have that kind of patience. Instead, I’ll provide a source for that writer down the road: a portrait of the village as it is today, a look at some of the surrounding area, and a discussion of the only game in town, making wine. The interesting thing about this for me is how much personal taste and philosophy determine the final product. Every winemaker will tell you that the wine she is making truly expresses the terroir from which it comes; yet there are huge differences in wines from the same place. I realize that even a small difference in location, even within the same vineyard, can make a difference in the wine, but the more profound differences come from the mind of the winemaker.

Here’s how Larry Walker put it in an email:

“Maury Grenache will produce what it is told to produce within certain limits. Those limits are very flexible and are set by the will of the winemaker: how ripe do I let these grapes get? How long do I leave them on the skins? How long in oak and what % of new oak–and there are a lot of other details but those are the Big Three: grape ripeness, skin contact, barrel treatment.”

I’ve produced a first step book through Blurb that I originally thought I’d use as a portfolio sample to try to persuade tourist and trade organizations to sponsor the book by agreeing to buy a substantial number of copies. Now I think I’m just going to produce the book I want to make and then see if anyone’s interested in publishing it, which is kind of how this whole thing started.