Mom is 97 years old, suffering from severe dementia; her mind is no longer connected to reality, yet the burden of her body continues. One dark, unseeing eye bulges out of her head; the other struggles to focus through a cataract. She cannot hear much. Her arms are covered with purple bruises, her legs bandaged to cover skin too thin to protect her. She is tiny, except for a severely bloated stomach that houses the tumor that refuses to kill her.

Her thoughts are trapped somewhere between disappointment and fantasy, in a world that never existed. It was never a happy life and that it continues in this painful demented manner is a terribly cruel punishment. She lost her parents at the age of twelve: her mother died, her father sent her away. She never recovered. Such an unhappy life that refuses to end.

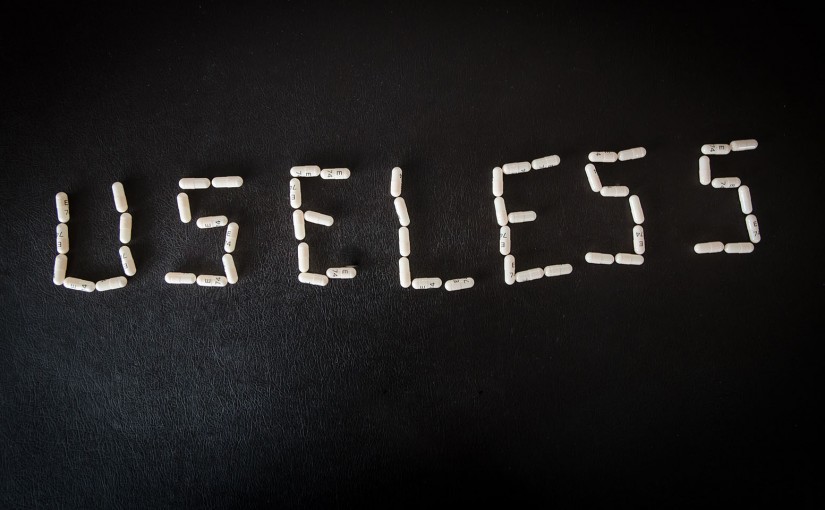

Yet there is nothing we can do. We cannot end her life. That decision is not for us to make. She is in pain, partially controlled by morphine. She is agitated: perhaps frustrated by growing mental incapacity, perhaps fearing death. Xanax helps a little. She is depressed, always has been, and there is Zoloft for that. This is maintenance, not life. We give her all these meds because she is demented and we fear she will succumb to the pain and despair and kill herself. What is rational behavior in this circumstance? Is it reasonable to preserve a worn out body by controlling a dysfunctional brain with drugs that render her senseless?

She can no longer make her wishes known to us, but this is consistent with a life-long pattern. In our family, no one ever makes clear what she really needs; we all persist in equivocating and deferring until we get what we want because some decision had to be made, or, more frequently, just move on, unsatisfied and slightly resentful. So mom wouldn’t tell us what she wanted when she was able, now she cannot.

She was frightened when we first arrived, not knowing my sister and I, perhaps thinking we were the ones who would take her away. I sat with her a while, holding her hand, offering what comfort I had to give. She became calmer. I wanted to will her to die. I told her to let go. She would fall asleep, I’d watch her breathe, wanting to make it stop. Then she’d wake with a small spasm, turn to me unable to see, not knowing who I was. Once she said she wanted to go home and I thought she really wanted to die, but it may be that she was still looking for a place for herself that she had never been able to find.

We were going to take her away, we came to move her to a home for people with dementia, but there’s not enough left to move. She is beyond the attention they would give her, more dead than alive.

There is nothing to be done. She has an aide who bathes her, feeds her, changes her diapers, and laughs at her plight in the kindest way. “That’s what they do when they get old,” she says, and then cleans up the mess. She makes her comfortable and mom kisses her hand in appreciation.

We don’t handle death very well in our culture, partly because we have huge industries manufacturing drugs and services whose sole purpose is the preservation of life, regardless of the quality of that life. We crucified Kevorkian and only a few states allow a person to choose the time and manner of death. We consider suicide to be insane. We need to rethink our priorities and reimagine our death. There comes a time, as in mom’s case, when preserving a useless body is the truly irrational act.